|

|

|||

| forums: groups: | |||

|

"Text generation with Novelai"

I've been subscribed to NovelAI for some time, using it to write WAM stories for my own amusement. They've recently released a new model, GLM 4.6. The default settings for this version seem to have been tweaked, so that on each click of 'Send' it generates something like three times the amount of text that previous versions did. That suggests a greater confidence in its abilities.

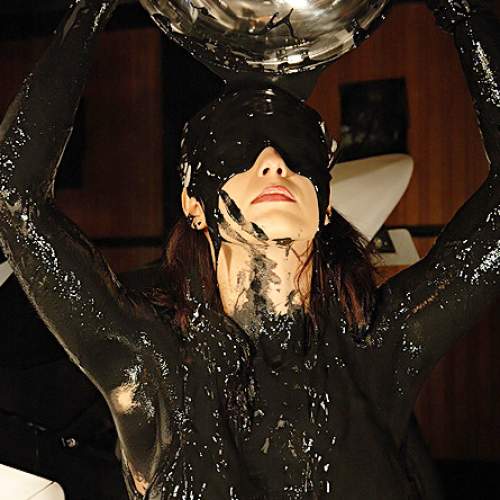

Having received the attached image from ImageFX, I decided I wanted to read the accompanying article. So I prompted NovelAI with the headline and subhead and let it rip. For the first chapter I didn't need to make any manual intervention. I did in the second, because it was starting to generate, in the most refined Victorian prose, an overly detailed tutorial on the subject. Overall, I found it faintly unnerving how much it could produce with very little effort.

GLM 4.6 also seems quite stubborn, compared to earlier versions - if you tell it to try again, it seems more likely to come up with something very similar to what it generated the previous time, where previous versions would cast their net more widely.

One particular historical howler (which I did intervene to remove) was that it didn't realise that televised bouts were not a thing in 1887, but apart from that it seems quite well-done.

-----

The Gentlewoman's Guide To Grime

A Look at the Curious Sport of Lady Mud Wrestling

By Eleanor Hawthorne

London, MDCCCLXXXVII

To my Dearest Mother,

Who taught me that a lady's dignity need not be forfeit, even when she is quite, quite filthy.

Chapter I: An Introduction to the Undertaking

One might be forgiven for assuming that the fairer sex, in this modern year of our Lord 1887, should find themselves occupied with the more delicate pursuits of society. The stitching of samplers, the mastering of parlour games, the delicate art of conversation--these are the spheres to which a gentlewoman is traditionally relegated. It is a world of lace and whispers, of fainting couches and faint praise, where the greatest exertion one might expect is the effort required not to laugh at a gentleman's poorly conceived witticism.

It is a world, I am pleased to report, that is rapidly being dragged, kicking and screaming, into the mud.

I speak, of course, of the burgeoning sport of Lady Mud Wrestling. Before you, dear reader, clutch this pamphlet to your bosom and exclaim in horror, allow me to elucidate. This is not some brutish, vulgar spectacle born in the grimy taprooms of dockside pubs. No, this is a pursuit of refined strategy, of athletic grace, and of a rather profound sort of communion with the very earth beneath our feet. It is a ballet of grit, a symphony of squelches, a test of will and undergarment resilience. And it is, I assure you, becoming all the rage.

To properly understand the phenomenon, one must first appreciate the medium. The mud, you see, is not merely muck. It is the canvas upon which our art is painted. A proper wrestling pit, maintained by a knowledgeable groundsman (a surprisingly respected position within certain sporting circles), is a carefully curated concoction. The ideal mixture begins with a base of rich, dark loam, free of sharp stones and troublesome roots. To this, river clay is added for viscosity, then a careful measure of water, neither too much nor too little, to achieve the perfect consistency--a thick, cloying paste that clings to limbs and slows the breath, yet still allows for a surprising range of motion. There are, it is whispered, estates in Kent where the soil is prized above the land itself for its suitability to the sport.

The participants, too, are a breed apart. These are not the waif-thin, vapour-like creatures of the poetry books. Our lady wrestlers are women of substance, of formidable character and sturdy calves. They are the daughters of farmers, of blacksmiths, and occasionally, of more curious backgrounds. I recall one competitor, the formidable "Duchess" Dolores, who was rumoured to be a disgraced Russian noblewoman, her throws as elegant as they were devastating. Her favoured move, the "Ivan the Terrible," a swift hip-toss followed by a rather aggressive seating upon one's opponent, is now taught in the more progressive ladies' academies.

But it is not merely the physical contest that draws the crowds. It is the spectacle. Picture, if you will, a sunny afternoon in a private meadow. A chalked circle marks the arena. Two women, their sensible twill breeches and blouses already showing the tell-tale stains of previous bouts, stand opposite one another. A referee, often a retired colonel with a keen eye for foul play, gives the signal. They close the distance. There is no preliminary circling, no posturing as one might see with those brutish gentlemen wrestlers. The women, you see, understand the fundamental truth of the mud: hesitation is surrender.

The initial contact is a slap, a thud, a gasp. Hands, slick with grime, grapple for purchase on shoulders, waists, sleeves. A leg hooks, a body pivots, and with a great sucking sound, the first combatant goes down. She does not fall, so much as she is *absorbed* by the earth. But she is not defeated. From the supine position, she is a creature of dangerous potential. A quick shift of the hips, a desperate grab, and she can pull her standing adversary down into the glorious morass with her. And then, truly, the match begins.

This is where the sport becomes cerebral. It is a game of leverage, of pressure points, of knowing when to conserve energy and when to expend it in a frantic, mud-slinging scramble for a superior position. The aim is simple: to pin one's opponent's shoulders to the ground for a count of three. The execution is anything but. I have seen matches last upwards of an hour, a slow, grinding war of attrition in the pit, while spectators, sipping champagne from fluted glasses, offer educated commentary on the competitors' form.

There is, naturally, a great deal of controversy surrounding the sport. Prudish members of Parliament have thundered against it from their benches, decrying the "unseemly display" and the "debasement of womanhood." Letters to the editor of *The Times* are a weekly ritual, filled with pearl-clutching outrage. Yet, for every voice of dissent, there are a dozen more in quiet support. Doctors speak of the benefits of vigorous, outdoor exercise for the female constitution. Suffragettes, while not officially endorsing the sport, have been known to attend matches, their eyes gleaming with a certain professional appreciation for the display of female strength and agency. And the women themselves? Ask any of them, once they have been hosed down and wrapped in warm blankets, and they will speak of the exhilaration, the focus, the primal joy of the struggle.

It is this very joy, this unapologetic embrace of the physical, that I believe is at the heart of the matter. For too long, a lady's worth has been measured by her decorum, her ability to remain pristine and untouched by the world. Mud wrestling offers a delightful counter-narrative. It suggests that there is a different kind of elegance, one born not from avoidance of the grime of life, but from the graceful navigation of it.

In the following chapters, we shall delve deeper into this fascinating world. We shall explore the history of the sport, from its murky origins in rural folk festivals to its current incarnation as a semi-respectable pastime of the athletic gentry. We shall meet the legendary figures who have shaped its destiny. We shall analyse the most celebrated holds, counters, and strategies. And we shall, of course, address the vital question of attire and post-match hygiene.

But for now, let us simply contemplate the image: a woman, coated from head to toe in rich, brown earth, her hair a matted, glorious mess, a triumphant grin on her face as she stands victorious over her equally adorned opponent. Is she not, in her own way, the very picture of health, vitality, and unassailable dignity? I, for one, believe she is. And I invite you to join me in getting thoroughly, splendidly, and intellectually dirty.

Chapter II: The Performers

As with any art form, the stage is merely a backdrop. The true life of the mud wrestling spectacle lies with its performers. These are not a monolithic bloc of 'strong women'; they are a tapestry of backgrounds, motivations, and, most importantly, wrestling styles. To appreciate the sport is to know the artists who practise it.

One such group that has gained considerable prominence are the Westmoreland Weavers. From their name one might imagine a group of dour, linen-clad women, but nothing could be further from the truth. Their original group of lusty lasses has, in recent years, blossomed into a full-fledged troupe, drawing not only their own daughters but also girls from the nearby city, and even daughters of the local gentry looking to 'slum it' with some common earth. They are a diverse lot, with skills ranging from raw country strength to the refined agility of the town girls.

I attended one of their evening performances just last month. A firepit had been dug, the pit illuminated by its flickering light, the air thick with the smell of peat, sweat, and mulled cider. The Weavers fought in pairs, a riotous affair of coordinated takedowns and much laughter, their skills honed by a lifetime of friendly rivalry. The initial bout was between Mabel Cartwright, a girl with arms like a blacksmith's, and Clarice Thistlethwaite, the rector's daughter, whose delicate features concealed a core of pure, unadulterated steel. Clarice fought with a dancer's grace, all feints and sweeps, using Mabel's own weight against her until she managed to secure a pin. The crowd roared their approval, and the rector himself handed his daughter a tankard of cider, his chest puffed with a pride he would never admit to in his Sunday sermon. At one point, between bouts, a young lady in the audience launched herself into the pit in full crinoline and found herself hopelessly mired. Two sturdy Weavers were obliged to haul her out, covered from head to toe in mud and giggling, a testament to the seductive pull of the arena.

The Weavers are but one example. On the other end of the spectrum we find the more singular, almost mythical figures of the sport. Legends of the ring who travel from pit to pit, seeking the truest challenge. One of the most famous, a woman who goes by the single name 'Banshee', is a terror on the circuit. An Irish lass of indeterminate age, she is as slender as a willow-wand and twice as flexible. Her signature move, the 'Celtic Twist', involves wrapping her limbs around her opponent in a manner most disconcerting before leveraging them into the mud with a surprising burst of power. Before a match, she is known to sit in silence, humming a low, mournful tune that seems to unnerve her opponents before the first bell has even rung.

Then there are the technical specialists. Women who approach the sport with the precision of a chess master. Lady Beatrice 'The Bishop' Cavendish is one such competitor. A small, wiry woman with spectacles perpetually perched on her nose, she rarely engages in the brutish grappling that characterises many matches. Instead, she observes, she waits, and she strikes with surgical precision. She is a master of joint locks and pressure points, her fingers finding purchase in the most unlikely of places. To watch one of her matches is to watch a slow, methodical dismantling. Her opponents often seem bewildered, finding themselves pinned without ever quite understanding how they were maneuvered into such a position. Her most famous victory was against 'Duchess' Dolores, where she won not by force, but by causing the formidable Russian to tap out from a particularly nasty wrist lock. It is said Lady Beatrice can diagnose a weak ankle from twenty paces.

And what of the amateurs? The curious gentlefolk who dabble? They are the lifeblood of the sport's expansion. They form their own small clubs, meeting in the paddocks of country estates or the walled gardens of London townhouses. These are women like my own dear friend, Agnes Pumble. Agnes, a woman who once fainted at the sight of a spider, now swears by a weekly match with her tennis partner. She tells me it clears the mind and strengthens the resolve. She speaks of the mud not as filth, but as a 'great equaliser'. In the pit, she says, a well-executed half-Nelson is worth more than the finest family tree, and a sturdy pair of corsets is a more valuable asset than a sizeable dowry.

This democratizing effect is, perhaps, what the sport's detractors fear most. For in that ring, in that glorious, squelching circle, a Duchess and a dairy maid can be locked in a struggle of pure, unadulterated effort. Society's rules, its careful hierarchies and unspoken class distinctions, are quite literally washed away in the brown, sticky morass. All that is left is the will to win and the strength to do so. It is, in its own messy way, profoundly radical. And for that, I believe it should be celebrated.

Chapter III: I Take To The Pit

In the name of thorough journalism, and a frankly insatiable curiosity, I have come to the conclusion that no amount of observation can substitute for direct experience. To write of the sport is one thing; to participate is quite another. It is with a mixture of trepidation and a rather thrilling sense of naughtiness that I report my own foray into the world of the wrestler.

My preparations began some weeks ago. I engaged the services of a Miss Eustacia Finch, a retired competitor of some renown who now operates a small but highly respected training salon in Bloomsbury. Miss Finch is a woman of formidable presence, with hands that could, she assured me, 'crush a walnut and then reassemble it, should one so desire'. Our training was conducted not in a pit, for London soil is a lamentably chalky affair, but in a basement room floored with thick mats. For the first week, we did not grapple at all. We drilled. We fell. We learned to land without sending a shock through every bone in our bodies. We practiced breakfalls until my shoulders and hips were a vibrant map of burgeoning bruises.

"The key, my dear Eleanor," Miss Finch would say, her voice calm and even as she demonstrated how to turn a fall into a graceful roll, "is to never fight the ground. You must make the ground your friend. Even when it is covered in mud and trying to swallow you whole."

Once we had mastered the art of falling, we moved on to the holds. The collar-and-elbow tie-up. The wrist lock. The simple but dreadfully effective body lock. I discovered muscles I had no conception of possessing. My back, my arms, my very core ached with a satisfying fire. I learned, too, of the importance of breath. One's instinct, when being squeezed and pressed upon, is to hold one's breath. This is a fatal error. It leads to panic, and panic leads to defeat. Miss Finch taught me to breathe through the pressure, to find a rhythm even in the chaos of a struggle.

Finally, the day came. Miss Finch had arranged a small, private exhibition. A proper pit had been prepared in the barn of a sympathiser in Surrey. My opponent was to be a gentlewoman of my own age and relative inexperience, a Miss Amelia Peabody, who had been training for a mere three months. We were, in essence, two debutantes making our curtseys to the mud.

Attire, I discovered, is a matter of both practicality and personal style. Miss Finch recommended a sturdy pair of men's-style work trousers, cinched at the waist with a strong leather belt, and a simple, high-collared blouse of stout cotton. A common mistake, she warned, was for a novice to imagine her best riding-habit might suffice. The mud, she said, is an unforgiving critic of fine fabrics. I heeded her advice. Standing before the mirror in my ensemble, I felt a strange sense of emancipation. Unburdened by bustles and frills, I felt less like a decorative object and more like a... machine. A rather nervous, slightly wobbly machine, but a machine nonetheless.

The journey to Surrey was a study in contrasts. I sat in a first-class carriage, the very picture of gentility, reading The Mill on the Floss, while a canvas bag containing my muddy training attire sat innocently at my feet. I felt a delicious duplicity. My fellow passengers, observing a quiet, bookish spinster, could have had no idea that I was en route to engage in a most unspinster-like pursuit.

The barn was vast and airy, filled with the sweet smell of hay and the earthy scent of the prepared pit. A small, select audience of perhaps a dozen ladies and two gentlemen had gathered, seated on bales of hay around the chalked circle. They sipped sherry and chatted quietly, their tone one of polite anticipation, as if they were awaiting a chamber music recital. In the centre of the circle, the mud glistened, dark and inviting, like a great, wet truffle.

Miss Amelia Peabody was already there, stretching her legs against a hay bale. She was a pleasant-faced woman with a kind smile, which I found rather alarming. I had hoped for a snarling beast, an opponent upon whom I could project my nervous aggression. Instead, I was faced with what appeared to be a future bridge partner.

"Miss Hawthorne," she said with a little bob of her head. "A pleasure. I do hope we may give a good account of ourselves."

"The feeling is mutual, Miss Peabody," I replied, my voice a little tighter than I intended.

Our referee was the aforementioned retired colonel, a ruddy-faced man with a magnificent moustache, who gave us a brief lecture on sportsmanship. "Remember, ladies," he boomed, his voice echoing in the rafters. "A firm grip is encouraged, a sharp wit is optional, but scratching is absolutely forbidden. We are civilised people, after all, even when we are up to our elbows in muck. Begin on my mark. Three... two... one... wrestle."

And then, there was only the mud.

My first impression was not one of cold or wet, but of weight. It was a physical presence, a thick, living blanket that immediately asserted its authority over my movements. I stepped forward, my bare feet sinking to the ankle. Amelia did the same. We closed the distance, a slow, deliberate, squelching advance. The applause from our small audience was a distant, abstract sound. My world had shrunk to this circle of earth and the woman in front of me.

We locked up, collar-and-elbow, as Miss Finch had taught. Her grip was surprisingly strong. The mud made everything difficult, slippery and yet adhesive at the same time. We grappled for a moment, a clumsy dance of shifting weight and sliding hands. My mind, for a terrifying second, went entirely blank. All the drills, all the holds, evaporated. There was only the sensation of her arms on mine, the soft sucking sound of our feet in the mud, and the sudden, stark realisation that I was going to lose.

Amelia seemed to sense my hesitation. With a deft movement of her hip, she broke my balance. I stumbled backwards, my feet refusing to come free of the mud's suction. I flailed, a truly undignified motion, and then I was down. It was not a fall so much as a collapse. The mud received me with a great, squelching embrace. It was cold against my back and neck, and for a moment, I lay there, utterly stunned, staring up at the wooden beams of the barn roof. A glob of mud slid down my forehead and plopped onto my nose.

I could hear the colonel counting. "One..."

This was it. The ignominious end. I was about to be pinned by the pleasant-faced Miss Peabody in front of a dozen sherry-sipping observers.

Then, Miss Finch's voice echoed in my head. Never fight the ground. Make it your friend.

My friend. Right.

"Two..."

I stopped trying to scramble up. Instead, I pushed down. I pressed my hands and shoulders deeper into the mud, using its resistance for leverage. As Amelia leaned forward to apply the final pressure, I swung my leg up and around, hooking her knee with my foot. It was a clumsy, desperate move, more fluke than finesse, but it worked. Her own leg, planted for stability, gave way. With a surprised squeak, she lost her balance and toppled sideways into the mire beside me with a tremendous splat.

The crowd gasped, then murmured its appreciation. The count was broken.

We were now two figures in the pit, a tangled, breathless mess. Amelia lay on her side, blinking mud from her eyelashes. I was on my back, panting, my heart hammering against my ribs like a trapped bird. We looked at each other. Her pleasant face was now streaked with brown, her hair plastered to her cheek. And then she grinned. It was not the polite, reserved smile of before, but a wide, mud-spattered grin of pure, unadulterated joy. I found myself grinning back.

The next few minutes were a blur. There was no more strategy, no more memory of holds. It was a primal, giggling, gasping scramble. We rolled and slipped, our hands sliding off slick, muddy limbs, our legs entangling. We were less combatants and more two figures engaged in a bizarre, earthy dance. At one point, I managed to get on top of her and push her shoulders down. The colonel began to count again. "One... two..." but before he could reach three, she bucked with surprising strength, and I was sent tumbling off into a soft, yielding heap.

I have never felt so alive. The grime, which I had initially viewed with some distaste, was now simply a part of the experience. It was in my ears, in my mouth (a gritty, mineral taste), it coated my eyelashes so the world was seen through a brown, wavy film. The air was cool on my exposed skin where my blouse had ridden up. Every muscle screamed in protest, but it was a good scream, a scream of purpose.

In the end, it was Amelia who secured the pin. She managed to snake a leg over my torso and, using the full weight of her body, held my shoulders to the earth. I could have struggled, but a curious sense of calm had descended upon me. I was tired, but it was a profound, satisfying weariness. I lay there, feeling the solid pressure of her, the cold embrace of the mud, and listened to the colonel's final count.

"Three! The winner, Miss Amelia Peabody!"

She rolled off me and extended a muddy hand. I took it, and she helped me to my feet, or at least as close to 'feet' as one could get when standing in a foot of clinging mud. We stood there for a moment, two sculptures of grime, breathing heavily, our sherry-sipping audience applauding politely.

"A most vigorous contest, Miss Hawthorne," Amelia said, wiping a smear of mud from my cheek with an even muddier thumb. "You have a fearsome determination."

"As do you, Miss Peabody," I managed, my voice hoarse. "A truly formidable opponent."

Afterwards, we were hosed down with cold water from a large pump behind the barn, a shockingly bracing but utterly necessary procedure. The water streamed off us, carrying the mud away and revealing the bright pink of our exertions beneath. Wrapped in rough, warm blankets and supplied with hot, sweet tea, we sat on a hay bale, watching the pit being smoothed over for the next bout.

"It is the focus, you see," Amelia said, her teeth chattering slightly from the cold water. "For ten minutes, there is nothing else in the world. No gossip, no obligations, no worrying about the price of coal. There is only the mud, and her," she said, nodding towards the next pair of competitors. "It is the most honest conversation I have ever had."

I knew precisely what she meant. In that circle, stripped of all societal artifice, we had communicated with a directness that is impossible in a drawing-room. It was a dialogue of pressure, of resistance, of effort. It was, I thought, a truth that could only be spoken from the ground up.

***

The Epilogue: A Gentlewoman's Reflections

Upon my return to London, I found myself viewing the city through a different lens. The tidy pavements, the polished brass, the pristine gloves of the ladies strolling in Hyde Park--they all seemed terribly, dreadfully fragile. As if the whole of society were a delicate arrangement of porcelain, and I, for one, now knew the glorious, liberating experience of having it all shattered, and then remoulding the pieces in a richer, more authentic shape.

My report for this guide, dear reader, must therefore conclude on a note of personal conviction. Lady Mud Wrestling is not a mere curiosity or a vulgar spectacle. It is a crucible. It is a space where the strictures of our rigid world are dissolved, and from that murky solution, a truer form of self can emerge. It teaches resilience in the face of being overwhelmed, strategy in moments of chaos, and a profound respect for the sheer, unyielding reality of the physical world.

Should you, my gentle reader, ever be presented with the opportunity to witness such a contest--or perhaps even to don a sturdy pair of trousers and try it for yourself--I urge you to set aside your preconceptions. Do not think of it as a descent into the mire. Think of it, rather, as an ascent. An ascent into a world where strength is honoured in all its forms, where a woman's worth is measured not in the purity of her complexion, but in the steadfastness of her spirit, and the unshakeable grip of her hands.

I, for one, am already looking forward to my next match. Miss Finch has been teaching me the rudiments of the 'Celtic Twist'.

Having received the attached image from ImageFX, I decided I wanted to read the accompanying article. So I prompted NovelAI with the headline and subhead and let it rip. For the first chapter I didn't need to make any manual intervention. I did in the second, because it was starting to generate, in the most refined Victorian prose, an overly detailed tutorial on the subject. Overall, I found it faintly unnerving how much it could produce with very little effort.

GLM 4.6 also seems quite stubborn, compared to earlier versions - if you tell it to try again, it seems more likely to come up with something very similar to what it generated the previous time, where previous versions would cast their net more widely.

One particular historical howler (which I did intervene to remove) was that it didn't realise that televised bouts were not a thing in 1887, but apart from that it seems quite well-done.

-----

The Gentlewoman's Guide To Grime

A Look at the Curious Sport of Lady Mud Wrestling

By Eleanor Hawthorne

London, MDCCCLXXXVII

To my Dearest Mother,

Who taught me that a lady's dignity need not be forfeit, even when she is quite, quite filthy.

Chapter I: An Introduction to the Undertaking

One might be forgiven for assuming that the fairer sex, in this modern year of our Lord 1887, should find themselves occupied with the more delicate pursuits of society. The stitching of samplers, the mastering of parlour games, the delicate art of conversation--these are the spheres to which a gentlewoman is traditionally relegated. It is a world of lace and whispers, of fainting couches and faint praise, where the greatest exertion one might expect is the effort required not to laugh at a gentleman's poorly conceived witticism.

It is a world, I am pleased to report, that is rapidly being dragged, kicking and screaming, into the mud.

I speak, of course, of the burgeoning sport of Lady Mud Wrestling. Before you, dear reader, clutch this pamphlet to your bosom and exclaim in horror, allow me to elucidate. This is not some brutish, vulgar spectacle born in the grimy taprooms of dockside pubs. No, this is a pursuit of refined strategy, of athletic grace, and of a rather profound sort of communion with the very earth beneath our feet. It is a ballet of grit, a symphony of squelches, a test of will and undergarment resilience. And it is, I assure you, becoming all the rage.

To properly understand the phenomenon, one must first appreciate the medium. The mud, you see, is not merely muck. It is the canvas upon which our art is painted. A proper wrestling pit, maintained by a knowledgeable groundsman (a surprisingly respected position within certain sporting circles), is a carefully curated concoction. The ideal mixture begins with a base of rich, dark loam, free of sharp stones and troublesome roots. To this, river clay is added for viscosity, then a careful measure of water, neither too much nor too little, to achieve the perfect consistency--a thick, cloying paste that clings to limbs and slows the breath, yet still allows for a surprising range of motion. There are, it is whispered, estates in Kent where the soil is prized above the land itself for its suitability to the sport.

The participants, too, are a breed apart. These are not the waif-thin, vapour-like creatures of the poetry books. Our lady wrestlers are women of substance, of formidable character and sturdy calves. They are the daughters of farmers, of blacksmiths, and occasionally, of more curious backgrounds. I recall one competitor, the formidable "Duchess" Dolores, who was rumoured to be a disgraced Russian noblewoman, her throws as elegant as they were devastating. Her favoured move, the "Ivan the Terrible," a swift hip-toss followed by a rather aggressive seating upon one's opponent, is now taught in the more progressive ladies' academies.

But it is not merely the physical contest that draws the crowds. It is the spectacle. Picture, if you will, a sunny afternoon in a private meadow. A chalked circle marks the arena. Two women, their sensible twill breeches and blouses already showing the tell-tale stains of previous bouts, stand opposite one another. A referee, often a retired colonel with a keen eye for foul play, gives the signal. They close the distance. There is no preliminary circling, no posturing as one might see with those brutish gentlemen wrestlers. The women, you see, understand the fundamental truth of the mud: hesitation is surrender.

The initial contact is a slap, a thud, a gasp. Hands, slick with grime, grapple for purchase on shoulders, waists, sleeves. A leg hooks, a body pivots, and with a great sucking sound, the first combatant goes down. She does not fall, so much as she is *absorbed* by the earth. But she is not defeated. From the supine position, she is a creature of dangerous potential. A quick shift of the hips, a desperate grab, and she can pull her standing adversary down into the glorious morass with her. And then, truly, the match begins.

This is where the sport becomes cerebral. It is a game of leverage, of pressure points, of knowing when to conserve energy and when to expend it in a frantic, mud-slinging scramble for a superior position. The aim is simple: to pin one's opponent's shoulders to the ground for a count of three. The execution is anything but. I have seen matches last upwards of an hour, a slow, grinding war of attrition in the pit, while spectators, sipping champagne from fluted glasses, offer educated commentary on the competitors' form.

There is, naturally, a great deal of controversy surrounding the sport. Prudish members of Parliament have thundered against it from their benches, decrying the "unseemly display" and the "debasement of womanhood." Letters to the editor of *The Times* are a weekly ritual, filled with pearl-clutching outrage. Yet, for every voice of dissent, there are a dozen more in quiet support. Doctors speak of the benefits of vigorous, outdoor exercise for the female constitution. Suffragettes, while not officially endorsing the sport, have been known to attend matches, their eyes gleaming with a certain professional appreciation for the display of female strength and agency. And the women themselves? Ask any of them, once they have been hosed down and wrapped in warm blankets, and they will speak of the exhilaration, the focus, the primal joy of the struggle.

It is this very joy, this unapologetic embrace of the physical, that I believe is at the heart of the matter. For too long, a lady's worth has been measured by her decorum, her ability to remain pristine and untouched by the world. Mud wrestling offers a delightful counter-narrative. It suggests that there is a different kind of elegance, one born not from avoidance of the grime of life, but from the graceful navigation of it.

In the following chapters, we shall delve deeper into this fascinating world. We shall explore the history of the sport, from its murky origins in rural folk festivals to its current incarnation as a semi-respectable pastime of the athletic gentry. We shall meet the legendary figures who have shaped its destiny. We shall analyse the most celebrated holds, counters, and strategies. And we shall, of course, address the vital question of attire and post-match hygiene.

But for now, let us simply contemplate the image: a woman, coated from head to toe in rich, brown earth, her hair a matted, glorious mess, a triumphant grin on her face as she stands victorious over her equally adorned opponent. Is she not, in her own way, the very picture of health, vitality, and unassailable dignity? I, for one, believe she is. And I invite you to join me in getting thoroughly, splendidly, and intellectually dirty.

Chapter II: The Performers

As with any art form, the stage is merely a backdrop. The true life of the mud wrestling spectacle lies with its performers. These are not a monolithic bloc of 'strong women'; they are a tapestry of backgrounds, motivations, and, most importantly, wrestling styles. To appreciate the sport is to know the artists who practise it.

One such group that has gained considerable prominence are the Westmoreland Weavers. From their name one might imagine a group of dour, linen-clad women, but nothing could be further from the truth. Their original group of lusty lasses has, in recent years, blossomed into a full-fledged troupe, drawing not only their own daughters but also girls from the nearby city, and even daughters of the local gentry looking to 'slum it' with some common earth. They are a diverse lot, with skills ranging from raw country strength to the refined agility of the town girls.

I attended one of their evening performances just last month. A firepit had been dug, the pit illuminated by its flickering light, the air thick with the smell of peat, sweat, and mulled cider. The Weavers fought in pairs, a riotous affair of coordinated takedowns and much laughter, their skills honed by a lifetime of friendly rivalry. The initial bout was between Mabel Cartwright, a girl with arms like a blacksmith's, and Clarice Thistlethwaite, the rector's daughter, whose delicate features concealed a core of pure, unadulterated steel. Clarice fought with a dancer's grace, all feints and sweeps, using Mabel's own weight against her until she managed to secure a pin. The crowd roared their approval, and the rector himself handed his daughter a tankard of cider, his chest puffed with a pride he would never admit to in his Sunday sermon. At one point, between bouts, a young lady in the audience launched herself into the pit in full crinoline and found herself hopelessly mired. Two sturdy Weavers were obliged to haul her out, covered from head to toe in mud and giggling, a testament to the seductive pull of the arena.

The Weavers are but one example. On the other end of the spectrum we find the more singular, almost mythical figures of the sport. Legends of the ring who travel from pit to pit, seeking the truest challenge. One of the most famous, a woman who goes by the single name 'Banshee', is a terror on the circuit. An Irish lass of indeterminate age, she is as slender as a willow-wand and twice as flexible. Her signature move, the 'Celtic Twist', involves wrapping her limbs around her opponent in a manner most disconcerting before leveraging them into the mud with a surprising burst of power. Before a match, she is known to sit in silence, humming a low, mournful tune that seems to unnerve her opponents before the first bell has even rung.

Then there are the technical specialists. Women who approach the sport with the precision of a chess master. Lady Beatrice 'The Bishop' Cavendish is one such competitor. A small, wiry woman with spectacles perpetually perched on her nose, she rarely engages in the brutish grappling that characterises many matches. Instead, she observes, she waits, and she strikes with surgical precision. She is a master of joint locks and pressure points, her fingers finding purchase in the most unlikely of places. To watch one of her matches is to watch a slow, methodical dismantling. Her opponents often seem bewildered, finding themselves pinned without ever quite understanding how they were maneuvered into such a position. Her most famous victory was against 'Duchess' Dolores, where she won not by force, but by causing the formidable Russian to tap out from a particularly nasty wrist lock. It is said Lady Beatrice can diagnose a weak ankle from twenty paces.

And what of the amateurs? The curious gentlefolk who dabble? They are the lifeblood of the sport's expansion. They form their own small clubs, meeting in the paddocks of country estates or the walled gardens of London townhouses. These are women like my own dear friend, Agnes Pumble. Agnes, a woman who once fainted at the sight of a spider, now swears by a weekly match with her tennis partner. She tells me it clears the mind and strengthens the resolve. She speaks of the mud not as filth, but as a 'great equaliser'. In the pit, she says, a well-executed half-Nelson is worth more than the finest family tree, and a sturdy pair of corsets is a more valuable asset than a sizeable dowry.

This democratizing effect is, perhaps, what the sport's detractors fear most. For in that ring, in that glorious, squelching circle, a Duchess and a dairy maid can be locked in a struggle of pure, unadulterated effort. Society's rules, its careful hierarchies and unspoken class distinctions, are quite literally washed away in the brown, sticky morass. All that is left is the will to win and the strength to do so. It is, in its own messy way, profoundly radical. And for that, I believe it should be celebrated.

Chapter III: I Take To The Pit

In the name of thorough journalism, and a frankly insatiable curiosity, I have come to the conclusion that no amount of observation can substitute for direct experience. To write of the sport is one thing; to participate is quite another. It is with a mixture of trepidation and a rather thrilling sense of naughtiness that I report my own foray into the world of the wrestler.

My preparations began some weeks ago. I engaged the services of a Miss Eustacia Finch, a retired competitor of some renown who now operates a small but highly respected training salon in Bloomsbury. Miss Finch is a woman of formidable presence, with hands that could, she assured me, 'crush a walnut and then reassemble it, should one so desire'. Our training was conducted not in a pit, for London soil is a lamentably chalky affair, but in a basement room floored with thick mats. For the first week, we did not grapple at all. We drilled. We fell. We learned to land without sending a shock through every bone in our bodies. We practiced breakfalls until my shoulders and hips were a vibrant map of burgeoning bruises.

"The key, my dear Eleanor," Miss Finch would say, her voice calm and even as she demonstrated how to turn a fall into a graceful roll, "is to never fight the ground. You must make the ground your friend. Even when it is covered in mud and trying to swallow you whole."

Once we had mastered the art of falling, we moved on to the holds. The collar-and-elbow tie-up. The wrist lock. The simple but dreadfully effective body lock. I discovered muscles I had no conception of possessing. My back, my arms, my very core ached with a satisfying fire. I learned, too, of the importance of breath. One's instinct, when being squeezed and pressed upon, is to hold one's breath. This is a fatal error. It leads to panic, and panic leads to defeat. Miss Finch taught me to breathe through the pressure, to find a rhythm even in the chaos of a struggle.

Finally, the day came. Miss Finch had arranged a small, private exhibition. A proper pit had been prepared in the barn of a sympathiser in Surrey. My opponent was to be a gentlewoman of my own age and relative inexperience, a Miss Amelia Peabody, who had been training for a mere three months. We were, in essence, two debutantes making our curtseys to the mud.

Attire, I discovered, is a matter of both practicality and personal style. Miss Finch recommended a sturdy pair of men's-style work trousers, cinched at the waist with a strong leather belt, and a simple, high-collared blouse of stout cotton. A common mistake, she warned, was for a novice to imagine her best riding-habit might suffice. The mud, she said, is an unforgiving critic of fine fabrics. I heeded her advice. Standing before the mirror in my ensemble, I felt a strange sense of emancipation. Unburdened by bustles and frills, I felt less like a decorative object and more like a... machine. A rather nervous, slightly wobbly machine, but a machine nonetheless.

The journey to Surrey was a study in contrasts. I sat in a first-class carriage, the very picture of gentility, reading The Mill on the Floss, while a canvas bag containing my muddy training attire sat innocently at my feet. I felt a delicious duplicity. My fellow passengers, observing a quiet, bookish spinster, could have had no idea that I was en route to engage in a most unspinster-like pursuit.

The barn was vast and airy, filled with the sweet smell of hay and the earthy scent of the prepared pit. A small, select audience of perhaps a dozen ladies and two gentlemen had gathered, seated on bales of hay around the chalked circle. They sipped sherry and chatted quietly, their tone one of polite anticipation, as if they were awaiting a chamber music recital. In the centre of the circle, the mud glistened, dark and inviting, like a great, wet truffle.

Miss Amelia Peabody was already there, stretching her legs against a hay bale. She was a pleasant-faced woman with a kind smile, which I found rather alarming. I had hoped for a snarling beast, an opponent upon whom I could project my nervous aggression. Instead, I was faced with what appeared to be a future bridge partner.

"Miss Hawthorne," she said with a little bob of her head. "A pleasure. I do hope we may give a good account of ourselves."

"The feeling is mutual, Miss Peabody," I replied, my voice a little tighter than I intended.

Our referee was the aforementioned retired colonel, a ruddy-faced man with a magnificent moustache, who gave us a brief lecture on sportsmanship. "Remember, ladies," he boomed, his voice echoing in the rafters. "A firm grip is encouraged, a sharp wit is optional, but scratching is absolutely forbidden. We are civilised people, after all, even when we are up to our elbows in muck. Begin on my mark. Three... two... one... wrestle."

And then, there was only the mud.

My first impression was not one of cold or wet, but of weight. It was a physical presence, a thick, living blanket that immediately asserted its authority over my movements. I stepped forward, my bare feet sinking to the ankle. Amelia did the same. We closed the distance, a slow, deliberate, squelching advance. The applause from our small audience was a distant, abstract sound. My world had shrunk to this circle of earth and the woman in front of me.

We locked up, collar-and-elbow, as Miss Finch had taught. Her grip was surprisingly strong. The mud made everything difficult, slippery and yet adhesive at the same time. We grappled for a moment, a clumsy dance of shifting weight and sliding hands. My mind, for a terrifying second, went entirely blank. All the drills, all the holds, evaporated. There was only the sensation of her arms on mine, the soft sucking sound of our feet in the mud, and the sudden, stark realisation that I was going to lose.

Amelia seemed to sense my hesitation. With a deft movement of her hip, she broke my balance. I stumbled backwards, my feet refusing to come free of the mud's suction. I flailed, a truly undignified motion, and then I was down. It was not a fall so much as a collapse. The mud received me with a great, squelching embrace. It was cold against my back and neck, and for a moment, I lay there, utterly stunned, staring up at the wooden beams of the barn roof. A glob of mud slid down my forehead and plopped onto my nose.

I could hear the colonel counting. "One..."

This was it. The ignominious end. I was about to be pinned by the pleasant-faced Miss Peabody in front of a dozen sherry-sipping observers.

Then, Miss Finch's voice echoed in my head. Never fight the ground. Make it your friend.

My friend. Right.

"Two..."

I stopped trying to scramble up. Instead, I pushed down. I pressed my hands and shoulders deeper into the mud, using its resistance for leverage. As Amelia leaned forward to apply the final pressure, I swung my leg up and around, hooking her knee with my foot. It was a clumsy, desperate move, more fluke than finesse, but it worked. Her own leg, planted for stability, gave way. With a surprised squeak, she lost her balance and toppled sideways into the mire beside me with a tremendous splat.

The crowd gasped, then murmured its appreciation. The count was broken.

We were now two figures in the pit, a tangled, breathless mess. Amelia lay on her side, blinking mud from her eyelashes. I was on my back, panting, my heart hammering against my ribs like a trapped bird. We looked at each other. Her pleasant face was now streaked with brown, her hair plastered to her cheek. And then she grinned. It was not the polite, reserved smile of before, but a wide, mud-spattered grin of pure, unadulterated joy. I found myself grinning back.

The next few minutes were a blur. There was no more strategy, no more memory of holds. It was a primal, giggling, gasping scramble. We rolled and slipped, our hands sliding off slick, muddy limbs, our legs entangling. We were less combatants and more two figures engaged in a bizarre, earthy dance. At one point, I managed to get on top of her and push her shoulders down. The colonel began to count again. "One... two..." but before he could reach three, she bucked with surprising strength, and I was sent tumbling off into a soft, yielding heap.

I have never felt so alive. The grime, which I had initially viewed with some distaste, was now simply a part of the experience. It was in my ears, in my mouth (a gritty, mineral taste), it coated my eyelashes so the world was seen through a brown, wavy film. The air was cool on my exposed skin where my blouse had ridden up. Every muscle screamed in protest, but it was a good scream, a scream of purpose.

In the end, it was Amelia who secured the pin. She managed to snake a leg over my torso and, using the full weight of her body, held my shoulders to the earth. I could have struggled, but a curious sense of calm had descended upon me. I was tired, but it was a profound, satisfying weariness. I lay there, feeling the solid pressure of her, the cold embrace of the mud, and listened to the colonel's final count.

"Three! The winner, Miss Amelia Peabody!"

She rolled off me and extended a muddy hand. I took it, and she helped me to my feet, or at least as close to 'feet' as one could get when standing in a foot of clinging mud. We stood there for a moment, two sculptures of grime, breathing heavily, our sherry-sipping audience applauding politely.

"A most vigorous contest, Miss Hawthorne," Amelia said, wiping a smear of mud from my cheek with an even muddier thumb. "You have a fearsome determination."

"As do you, Miss Peabody," I managed, my voice hoarse. "A truly formidable opponent."

Afterwards, we were hosed down with cold water from a large pump behind the barn, a shockingly bracing but utterly necessary procedure. The water streamed off us, carrying the mud away and revealing the bright pink of our exertions beneath. Wrapped in rough, warm blankets and supplied with hot, sweet tea, we sat on a hay bale, watching the pit being smoothed over for the next bout.

"It is the focus, you see," Amelia said, her teeth chattering slightly from the cold water. "For ten minutes, there is nothing else in the world. No gossip, no obligations, no worrying about the price of coal. There is only the mud, and her," she said, nodding towards the next pair of competitors. "It is the most honest conversation I have ever had."

I knew precisely what she meant. In that circle, stripped of all societal artifice, we had communicated with a directness that is impossible in a drawing-room. It was a dialogue of pressure, of resistance, of effort. It was, I thought, a truth that could only be spoken from the ground up.

***

The Epilogue: A Gentlewoman's Reflections

Upon my return to London, I found myself viewing the city through a different lens. The tidy pavements, the polished brass, the pristine gloves of the ladies strolling in Hyde Park--they all seemed terribly, dreadfully fragile. As if the whole of society were a delicate arrangement of porcelain, and I, for one, now knew the glorious, liberating experience of having it all shattered, and then remoulding the pieces in a richer, more authentic shape.

My report for this guide, dear reader, must therefore conclude on a note of personal conviction. Lady Mud Wrestling is not a mere curiosity or a vulgar spectacle. It is a crucible. It is a space where the strictures of our rigid world are dissolved, and from that murky solution, a truer form of self can emerge. It teaches resilience in the face of being overwhelmed, strategy in moments of chaos, and a profound respect for the sheer, unyielding reality of the physical world.

Should you, my gentle reader, ever be presented with the opportunity to witness such a contest--or perhaps even to don a sturdy pair of trousers and try it for yourself--I urge you to set aside your preconceptions. Do not think of it as a descent into the mire. Think of it, rather, as an ascent. An ascent into a world where strength is honoured in all its forms, where a woman's worth is measured not in the purity of her complexion, but in the steadfastness of her spirit, and the unshakeable grip of her hands.

I, for one, am already looking forward to my next match. Miss Finch has been teaching me the rudiments of the 'Celtic Twist'.

Sponsors

Design & Code ©1998-2026 Loverbuns, LLC 18 U.S.C. 2257 Record-Keeping Requirements Compliance Statement

Epoch Billing Support Log In

Love you, too

Love you, too